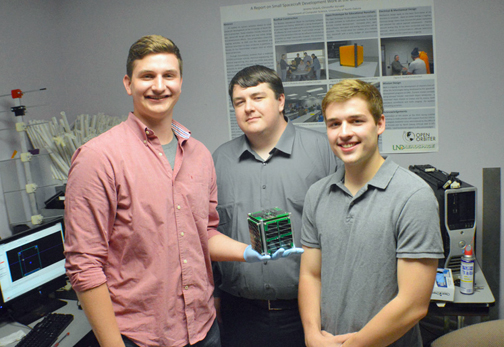

University of North Dakota graduate Michael Wegerson, left, joined by graduate Jeremy Straub and student Thomas McGuire hold the smallsat that was created and assembled by a group of university students over the course of several years. Photo by Brandi Jewett, Grand Forks Herald.

Brandi Jewett posted a news story in North Dakota's Bismark Tribune infosite that reveals a trip to space is in the cards this year for a homemade University of North Dakota satellite.

However, according to Jewett, the students and alumni behind the small device said its purpose extends beyond orbiting Earth. The smallsat started as an idea in 2011 among a group of students who were seeking to create a project that could prove helpful to a larger community of learners.

The OpenOrbiter Small Spacecraft Development Initiative was born and the satellite's progress has been advanced by hundreds of students over the years with the goal of sending a CubeSat into space and creating a design that could be used as a platform for other, similar projects. This year, the project reached a major milestone with its initial fit check, meaning all of the spacecraft’s components were assembled for the first time.

Come December, members of the project team hope to have their creation hitch a ride to the International Space Station, where the likelihood is that a NASA astronaut will launch the satellite into space early next year.

“We finally came up with making a satellite that makes it easier for everyone else to make a satellite,” said Jeremy Straub, the project’s director and a recent doctoral graduate of the school’s computer science program.

“We completed most of the primary electrical system work for the satellite,” said Michael Wegerson, a project member and recent graduate from UND’s electrical engineering program. “We’re just figuring out a few final tweaks and a few final bugs we’ve found in our design, and we’re working and ironing those out. We’re really close.”

The project, which has had a core group of 90 or so contributors throughout its lifetime, has headquarters on the first floor of University of North Dakota's Streibel Hall. The CubeSat is not housed in a spacious lab but rather in a small room that team members affectionately call the “Cube Closet.” Inside are a variety of tools, both purchased and improvised, that students have used to design and create parts for the satellite. Some are the usual tools of the engineering trade but, in an attempt to keep costs down, students have repurposed items of their own, including crafting stencils from pop cans and using a microwave oven to weld components together.

Keeping costs down is a key part of the project, which aims to create a satellite for less than $5,000. There are kits available the group could have used to build a similar device, but those can start at around $50,000. Receiving enough funding consistently to purchase components can be difficult, so OpenOrbiter members sought to find a more inexpensive way to build a satellite through extensive planning sessions.

“As we broke it down further and further, the answer that we came up with is there’s not really a whole lot of expense here, it’s just knowledge that’s kind of packed into the design, not really the components,” Straub said.

So far, the satellite has an estimated price tag of about $2,500 to $3,000. Getting the smallsat into space will cost money, but NASA will foot that bill. UND’s project took top honors in a competition hosted by NASA’s Educational Launch of Nanosatellites program, winning a free ride into space. The integration of the satellite to the space station will be handled by NanoRacks, a company that provides clients’ services and hardware a path to the station. Straub, Wegerson and others involved hope to watch their creation launch from a camera held by an astronaut.

Though the process from concept to design to creation has required long hours, participants said the experience has been invaluable. Thomas McQuire, a mechanical engineering student, said he’s spent much of his time at UND working on the project and picking up skills along the way. He noted that he has gained a lot of random technical skills and just a lot of stuff that’s really going to help in the future that I wouldn't have gotten by just going to class and working on stuff that way,” he said.

Employers look highly on the experiential learning aspect of the project, Wegerson said, attributing his success in securing two internships to his work with the satellite. For those involved with the initiative, it’s a constant exercise in problem solving as the group follows very specific parameters for creating and assembling parts.

“If it doesn’t fit in the launcher, it’s not going in the launcher,” Straub said. “Quite literally, there is not a whole lot of wiggle room.”

Wegerson and others also are working on a business concept that would sell their satellite design and components to allow for varying degrees of customization. Once completed and refined, the group hopes to see its satellite built by various users, such as high school classes.

“It’s one of the perks of our design,” Wegerson said. “The entire thing is open source so they can do what they want. They can take our stuff or they can take our standard and design their own stuff.”