Another satellite launch will take place next week, this time it will be a Chinese satellite, TanSat, built to monitor carbon and the global distribution of the same—and not a moment too soon as the nation is one of the worst offenders. Dramatic photos are making their way into the world's news as China is suffering terrible smog bouts, with people decked out in medical masks and buildings are barely visible in the background.

Named TanSat, as 'tan' is the Chinese word for carbon, the satellite is set to launch on a two-stage hypergolic Long March 2D carrier rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in the Gobi Desert. Launch time is currently unconfirmed, but expected around 19:15 UTC on December 21, or 03:15 December 22 local time. TanSat will improve the understanding of global CO2distribution, beginning with its role in the carbon cycle and the ultimate contribution to climate change, and also track efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions. The satellite is funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and implemented by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

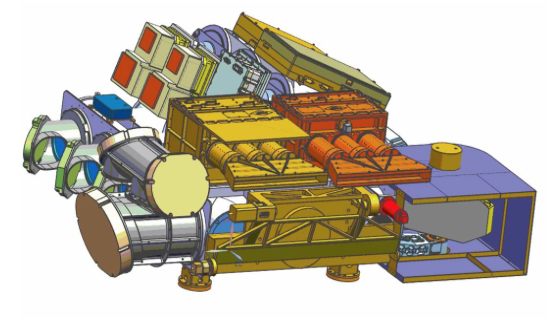

TanSat payloads undergoing testing (CIOMP).

The 620kg satellite will enter a 700km altitude Sun-synchronous orbit, where it is expected to operate for at least three years, with a revisit time of 16 days.

Tansat carries two main instruments: a high-resolution Carbon Dioxide Spectrometer for measuring the near-infrared absorption by CO2, and a Cloud and Aerosol Polarimetry Imager (CAPI) to compensate the CO2 measurement errors by high-resolution measurement of cloud and aerosol. According to the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics (CIOMP) under CAS, which developed the instruments, the CO2 detector will use optical remote sensing technology to examine the concentration of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the air, while the atmospheric particulate matter sensor will analyze cloud and particulate matter to support the calculation of CO2 distribution.

Under the Paris climate deal agreed in December 2015 and ratified by China in September, the country has pledged to peak CO2 emissions by 2030 or earlier, and reduce CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by 60 to 65 percent from 2005 levels over the same time.

From the beginning of the industrial age, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 has increased from about 280 parts per million to over 400 ppm.

Zhengzhou, capital of Henan province, suffering haze on December 12. (Photo: CNS)

China is now the largest annual emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs), and as the photo shows its cities are often afflicted by heavy smog. The United States remains the largest historical contributor to global GHG emissions.

TanSat will operate in different modes depending on whether the satellite is making observations over land or oceans and lighting conditions.

China had planned to use TanSat in concert with satellites from other actors, including those of the United States and European Space Agency, with talks taking place in the summer.

The satellite platform carrying the instruments was developed by the Shanghai Institute of Microsystems and Information Technology (SIMIT), while the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) is responsible for the ground segment, which will receive and validate observation data.

The University of Leicester and University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom are international partners in the project.

TanSat payload diagram (CIOMP).

A successful launch would mean a record 20th success for China in a calendar year. One failure, an underperforming third stage in during the launch of Gaofen-10 in September, means that while China made a national record 20 launches in 2016, it currently ties with 2012 and 2015 on 19 successful launches.

TanSat could be followed by another three launches in an intense finish to a massive year, including Gaojing-1 remote sensing satellites from Taiyuan, Jilin-1 video satellite and smaller payloads from Jiuquan on a solid-fuelled Kuaizhou-1 rocket, and the TXJSSY-2 Communications Engineering Test Satellite on a Long March 3B from Xichang.

These would round off a breakthrough year that has seen the successful launch of two new cryogenic rockets, including the massive Long March 5, a human spaceflight mission, Shenzhou-11, in preparation for the country’s space station, and intriguing space science missions.