Owen Mace (left), Paul Dunn, Peter Hammer, Richard Tonkin and Rod Tucker, the brains behind Australis. Picture: Tony Gough

In 1957, the former Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, humanity’s first artificial satellite.

The launch began the space age as countries around the world raced to be the next to get a human-made object into orbit.

But the satellite also inspired a generation of kids whose horizons suddenly expanded beyond earth’s atmosphere.

For Owen Mace, an 11-year-old boy about to start boarding school in Geelong, it sparked an obsession that would lead him to join the Melbourne University Astronautical Society (MUAS), and eventually, to building and launching Australia’s first satellite.

“I was a complete nerd. But I arrived at university and there was a group of people who were just as absorbed,” the now Dr Owen Mace says.

Dr Mace was one of a group of 20 University of Melbourne students who met weekly as MUAS to discuss satellites, antennas, electronics and all things space.

“We’d discovered how to listen to various satellites and receive weather pictures on behalf of the Bureau of Meteorology.

“When someone asked, ‘Why not build our own satellite?’, we thought sure, why not.”

The students take delivery in the US

(their sign says God Save The Queen)

The fact that no one in Australia had made a satellite, let alone launched one, wasn’t an issue.

Told by the “grown-ups” that it couldn’t be done, the group did what all young 22 and 23-year-olds do — they ignored them.

“People we talked to all scoffed at us, they thought we were ridiculous,” says Richard Tonkin, another student who was involved in the project.

“When asked if it was an official project we happily replied no — we were just doing it, and we did.”

Realising there was no point simply building a satellite, it needed to be launched, the group wrote to one of two countries that had successfully launched satellites at that time — America.

“Australia had not demonstrated a satellite launching capability at that stage and the only countries that had launched satellites were the Soviet Union and America,” says Dr Mace.

“Obviously, the ‘baddies’ were not a consideration, even if we could speak their language, so an American launch was the only feasible option.”

Fortunately, the California-based Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio (OSCAR) organisation had already flown three satellites and was embarking on its fourth. They were happy to help.

“They replied to us and said if we built it, they’d try to launch it. And that’s all we needed, we went ahead immediately,” Mr Tonkin says.

But the project needed a name. And in 1965, Project Australis was born with its headquarters in the rooftop garret of the Natural Philosophy building in the University of Melbourne and a postal address care of the Student’s Union.

With virtually no budget, it was time to get this “harebrained” idea off the ground.

“Everything had to be donated, so Richard and I undertook a publicity campaign in the press, radio and television,” Dr Mace says.

But even so, resources were limited, so the group improvised.

“An oven in students’ digs was used for the high temperature tests and we still wonder if the Glaciology Department was aware that its freezer was purloined to check its operation at low temperatures,” Mr Tonkin says.

“Long before rules and regulations were developed in regards to flying balloons in commercial air space, we launched weather balloons from the roof of the Old Physics building to test transmitters, a command system and telemetry.”

The students prepare for a balloon flight using a weather balloon.

By mid-1967 Australis had been built and tested.

Dr Mace, Mr Tonkin and fellow undergraduate student Paul Dunn boarded a plane for a long flight to California.

“Once there were met with incredible hospitality and saw amazing technology sites including the Apollo modules being made and the first manned one,” says Dr Mace.

Despite the welcome, Australis wasn’t launched.

After laying dormant in a garage for over a year, in late 1968 a group at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Washington DC adopted Australis.

“We were back! Despite being in the midst of the Apollo moon landings in 1969, NASA management agreed to launch Australis. It helped that many of those managers were also amateur radio operators and had briefly read about the story of Australis,” Dr Mace says.

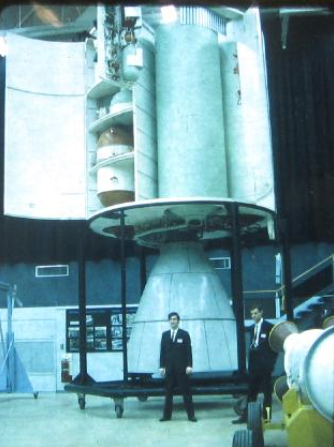

Owen Mace and Paul Dunn in front of a model of the Apollo Service Module.

After this renewed interest, things sped up. The batteries in Australis were refurbished and tested to ensure it would survive the launch and it was ready to go.

Owen Mace and Paul Dunn in front of a model of the Apollo Service Module.

On Friday, January 23, 1970, at 11.31am California time, Australis was launched as a secondary payload on a Delta rocket from Vandenberg air force Base.

“It came up over the horizon, we were waiting and waiting and suddenly, it was there, it was working. We did it,” Mr Tonkin says.

“In orbit, our baby became Australis OSCAR 5, or AO5 for short.”

Australis OSCAR 5, the first student-built satellite, operated successfully and orbited for over six weeks until the batteries exhausted.

One member of the team continued working with AMSAT, the Radio Amateur Satellite Corporation and built a complex command system that continues to operate today — the longest-surviving earth satellite command system, amateur or professional.

“A little part of the University of Melbourne is still circling overhead every couple of hours and will continue to do so for another hundred thousand years, give or take a few,” Dr Mace says.

Dr Owen Mace’s new book, Australis OSCAR 5: The Story of how Melbourne University Students Built Australia’s First Satellite, is available through ATF Press, atfpress.com.

Holly is a University of Melbourne media adviser. First published on pursuit.unimelb.edu.au