While the blockbuster film Gravity is wowing audiences with the tale of two astronauts bombarded by debris and set adrift in space, agencies across the world will be tracking the re-entry of a European satellite that won’t be adding to the 22,000 catalogued pieces of space junk currently orbiting our planet.

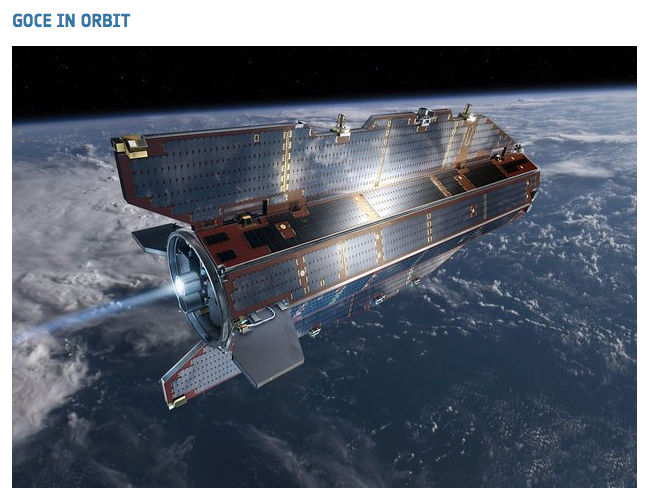

Due to return to Earth around November 6 , the GOCE Earth Explorer satellite, like most research satellites, is not equipped with a propulsion system that will allow a controlled re-entry over a remote region of the planet. While most of GOCE will disintegrate in the atmosphere, some smaller parts are expected to reach Earth’s surface. When and where these parts might land cannot yet be predicted, but the affected area will be narrowed down closer to the time of re-entry. This style of decommissioning may seem like a risky strategy but it’s actually one of the better options.

During the past 50 years, an average of one tracked piece of debris fell back to Earth each day. No serious injury or significant property damage by this re-entering debris has ever been confirmed. However, defunct satellites that are left in orbit have been known to cause damage to other working satellites.

These days, plans to safely decommission a satellite must be submitted during the licensing process and must adhere to a number of international space treaties including the Outer Space Treaty, the Rescue Agreement, the Liability Convention and the Registration Convention. These treaties form the basis for dealing with activities in outer space and inform related national legislation such as the Outer Space Act (1986) which reflects the UK’s international responsibilities and obligations involving the activities of its nationals in outer space.

When it comes to the decommissioning of satellites there are currently three options available: they can be de-orbited back to Earth like GOCE, they can be left where they are (if they pose no potential risk to other satellites), or they can be put in a graveyard orbit.

Due to their distance from Earth, geostationary satellites are disposed of in graveyard orbits above their operational altitude. This process reduces the chances of the satellite colliding with other operational spacecraft and lowers the risk of orbital debris.

For lower altitude satellites like GOCE, immediate satellite de-orbiting upon end-of-life is the safest option. Those that aren’t immediately de-orbited are adding to the problem of congestion and have the potential to become space debris. Now a major problem for the world’s space-faring nations, space junk can be very large, such as burnt-out rocket stages and dead spacecraft, or very small, such as flecks of paint.

Collisions with large pieces of junk can disable or even destroy a spacecraft, as happened to the French Cerise spacecraft in 1996. Smaller debris can also cause major damage or threaten spacewalking astronauts, as shown in the film Gravity.

When the Hubble Space Telescope’s solar panels were brought back to Earth in 2002, they were peppered with impact craters up to 8 mm across.

Today, telescopes and radar are monitoring around 22,000 pieces of junk down to 10 cm in size. Many millions of pieces are too small to be detected from the ground, such as flecks of paint and dust. Normally, these would not be a threat, but in space, debris travels at high speed. Even dust particles can act like tiny bullets.

Professor Richard Crowther, Chief Engineer at the UK Space Agency, said, “All space agencies now recognise the growing threat that orbital debris poses to satellites and the long term sustainability of space. With increasing demand for the many services that satellites deliver here on Earth, the space around our planet is set to become even more congested. To maintain our vital space infrastructure we must take further measures to prevent more debris, such as removing satellites from orbit at end of life.”

Besides the safe de-orbiting of satellites like GOCE, other measures are being taken to mitigate the problems caused by congestion and space debris. There are a number of projects to research new technologies for removing space debris and international bodies such as the UN and the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) have produced space debris mitigation guidelines.

For GOCE, with its planned re-entry, no new technology is required. The satellite is now being tracked by sensors around the world, and its journey back to Earth is being monitored through an international campaign.

This kind of space surveillance is especially important in today’s growing space market and is vital in the provision of prompt and precise information regarding objects orbiting the Earth. Using this data, a wide range of services can be provided – such as producing a catalogue of objects, charting the position and orbital paths of man-made objects, warning of potential collisions, and alerting when and where debris re-enters the Earth's atmosphere.