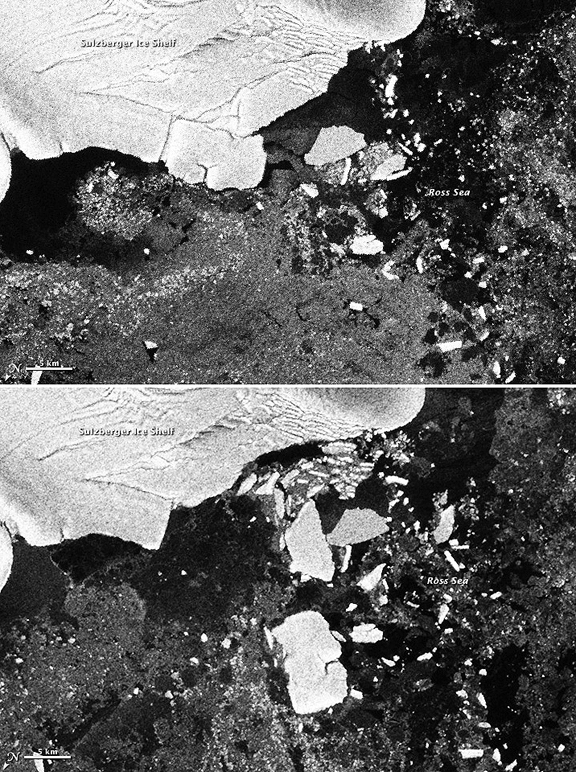

Scientists have long speculated that ocean waves could cause pieces of an ice shelf to flex and break, but this is the first time researchers have observed a tsunami affecting ice cover. The images below were acquired by the Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar (ASAR) on the European Space Agency’s Envisat satellite on March 11 and 16, 2011. The top image was taken just before the icebergs began to separate from the Sulzberger Ice Shelf, while the bottom image shows the chunks of ice well out to sea just five days later. This time-lapse series of images shows the progression of the ice breakup. In each radar image—which allows researchers to see through cloud cover—land ice, ice shelves, and the new bergs are brighter white, while grayer areas have smaller bits of sea ice. Open water is black.

Images courtesy of the European Space Agency.

Caption by Patrick Lynch and Mike Carlowicz.

Icebergs can form in any number of ways, but much of the time, the process is out of sight. Often, scientists see large chunks drifting in polar seas, and then have to work backwards to figure out the point of origin. In this case, a research team led by Kelly Brunt of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center looked ahead, not back. When the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami occurred off Japan on March 11, 2011, the ice researchers immediately looked south as the massive waves exploded out from the epicenter in the northwest Pacific Ocean. The scientists checked records for vulnerable faces of the Antarctic coast and studied models of the likely wave propagation. Within 18 hours of the tsunami, the waves had traveled 8,000 miles (13,600 kilometers) and reached the shores of Antarctica.

Using multiple satellite images, Kelly Brunt, Emile Okal of Northwestern University, and Douglas MacAyeal of the University of Chicago were able to observe two large new icebergs and many smaller bits floating in the Ross Sea off Antarctica just hours after the sea swell reached the continent. Together, the chunks of ice equaled an area of 125 square kilometers, about two times the size of Manhattan Island in New York. The swell from the Tohoku tsunami was likely only a foot high (30 cm) when it reached the Sulzberger Ice Shelf. But the consistency of the waves created enough stress to cause the calving. This particular stretch of floating ice shelf is about 260 feet (80 meters) thick, from its exposed surface to its submerged base. According to historical records, the piece of ice that broke loose on March 11 hadn't budged for at least 46 years before the tsunami came along.