VANDENBERG AFB, Calif. – Technicians work on the payload fairing that will protect NASA's Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) spacecraft during launch aboard an Orbital Sciences Pegasus XL rocket. Launch is currently scheduled no earlier than May 28, 2013. The IRIS satellite will improve our understanding of how heat and energy move through the deepest levels of the sun's atmosphere, thereby increasing our ability to forecast space weather. On launch day, deployment of the Pegasus from Orbital’s L-1011 carrier aircraft will occur at a location over the Pacific Ocean about 100 miles northwest of Vandenberg off the central coast of California south of Big Sur. Image Credit: VAFB/Randy Beaudoin

Understanding the interface between the photosphere and corona remains a fundamental challenge in solar and heliospheric science. The Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) mission opens a window of discovery into this crucial region by tracing the flow of energy and plasma through the chromosphere and transition region into the corona using spectrometry and imaging.

IRIS is designed to provide significant new information to increase the understanding of energy transport into the corona and solar wind and provide an archetype for all stellar atmospheres.

The unique instrument capabilities, coupled with state of the art 3-D modeling, will fill a large gap in our knowledge of this dynamic region of the solar atmosphere. The mission will extend the scientific output of existing heliophysics spacecraft that follow the effects of energy release processes from the sun to Earth.

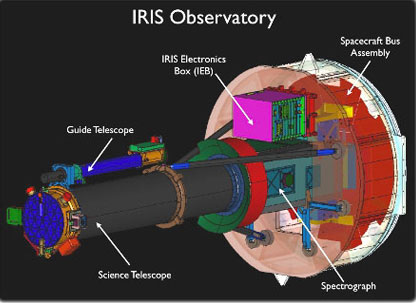

The IRIS satellite design is derived from several previous NASA/LMSAL spacecraft. By re-using prior designs Lockheed Martin was able to reduce technical, scheduling and cost risks. Solar arrays omitted for clarity. Credit: LMSAL

IRIS is NASA's Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph. Its primary goal is to understand how heat and energy move through the lower levels of the solar atmosphere.

IRIS is a class of spacecraft called a Small Explorer, which NASA defines as costing less than $120 million.

Lockheed Martin (LM) Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory in LM’s Advanced Technology Center is the principle investigator institution and has overall responsibility for the mission, with major contributions from Lockheed Martin Civil Space, NASA Ames, Smithsonian Astrophysical Laboratory, Montana State University, Stanford University and the University of Oslo.

IRIS weighs 440 pounds. It is approximately 7 feet (2.1 meters) long and, with its solar panels extended, is a little over 12 feet (3.7 meters) across.

IRIS will make use of high-resolution images, data and advanced computer models to unravel how matter, light, and energy move from the sun’s 6000 K surface to its million K outer atmosphere or corona. A fundamentally mysterious region that helps drive heat into the corona, this area has been notoriously hard to study. IRIS will be able to tease apart what's happening there better than has ever been done before.

To do this, IRIS will observe the lowest part of the sun's atmosphere: the chromosphere, an expanse of ionized gas or plasma lying just above the sun's surface, and the transition region, where the chromosphere transitions into the even hotter corona above. This interface region lies at the core of many outstanding questions about the sun's atmosphere, such as how the sun creates giant explosions like solar flares or coronal mass ejections (CMEs), or how solar material in the corona reaches millions of degrees, several thousand times hotter than the surface of the sun itself.

Much of this coronal heating begins in the chromosphere and transition region. These highly dynamic regions are constantly in motion, so it isn't simple to profile temperatures with respect to position. Indeed, a wide range of temperatures can occur at similar heights, with different swaths of material propelled upward and downward in response to the release of magnetic energy, as well as various types of plasma waves. This moving interface region covers a wide range of heights above the sun’s surface, extending over several thousand miles. Throughout this height range, not only do the temperatures vary dramatically from 5000 Kelvin to almost a million degrees, but there are also enormous density contrasts, with certain areas up to a million times more dense than others.

This turbulent interface region contains more mass than does all the rest of the corona and heliosphere, which extends to the very edge of the solar system. Given how much material is there, the chromosphere requires a heating rate at least ten times greater than that of the corona itself.

One of IRIS's main science objectives will be to study how this foundational region of the heliosphere contributes mass and energy to the atmosphere above it, depositing so much heat into the corona. IRIS observations will mesh with those from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which launched in 2010. SDO observes the sun's surface and the corona, while IRIS will observe the crucial region in between the photosphere and corona at much higher resolution than ever before captured. IRIS is what's called an imaging spectrograph, which means it will provide both images and what are called spectra, which splits light into its various colors. Each line of light carries information about different materials of the sun and how they move, thus they can be used to probe physical characteristics in the solar atmosphere such as density, temperature and velocity.

IRIS will attempt to distinguish between two mechanisms that may be responsible for powering this region: magnetic field reconnection and dissipation of waves that travel through the solar atmosphere. Both these phenomena can add to the turbulence of the region and IRIS’s high-resolution spectra and images will be able to tease apart just which forms of energy cause which effects.

Such information will also help scientists examine how the solar material and its attendant magnetic fields contribute to eruptions on the sun such as solar flares and CMEs. This may increase our ability to forecast such space weather, which can disable satellites, cause power grid failures, and disrupt GPS services.

Lastly, understanding our own star better will help deepen our insight into atmospheres at distant stars as well.