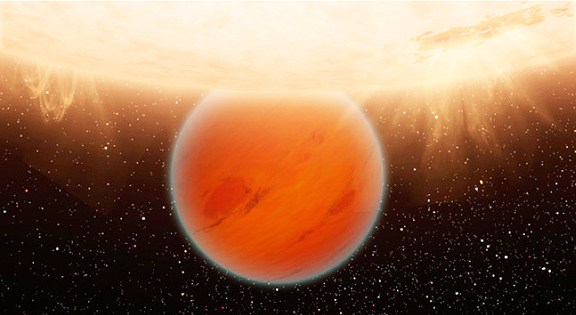

An unusual, methane-free world is partially eclipsed by its star in this artist's concept. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The methane-free planet, called GJ 436b, is about the size of Neptune, making it the smallest distant planet that any telescope has successfully "tasted," or analyzed. Eventually, a larger space telescope could use the same kind of technique to search smaller, Earth-like worlds for methane and other chemical signs of life, such as water, oxygen and carbon dioxide. Methane is present on our life-bearing planet, manufactured primarily by microbes living in cows and soaking in waterlogged rice fields. All of the giant planets in our solar system have methane too, despite their lack of cows. Neptune is blue because of this chemical, which absorbs red light. Methane is a common ingredient of relatively cool bodies, including "failed" stars, which are called brown dwarfs. In fact, any world with the common atmospheric mix of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen, and a temperature up to 1,000 Kelvin (1,340 degrees Fahrenheit) is expected to have a large amount of methane and a small amount of carbon monoxide. The carbon should "prefer" to be in the form of methane at these temperatures.

At 800 Kelvin (or 980 degrees Fahrenheit), GJ 436b is supposed to have abundant methane and little carbon monoxide. Spitzer observations have shown the opposite. The space telescope has captured the planet's light in six infrared wavelengths, showing evidence for carbon monoxide but not methane. GJ 436b is located 33 light-years away in the constellation Leo, the Lion. It rides in a tight, 2.64-day orbit around its small star, an "M-dwarf" much cooler than our sun. The planet transits, or crosses in front of, its star as viewed from Earth. Spitzer was able to detect the faint glow of GJ 436b by watching it slip behind its star, an event called a secondary eclipse. As the planet disappears, the total light observed from the star system drops — this drop is then measured to find the brightness of the planet at various wavelengths. The technique, first pioneered by Spitzer in 2005, has since been used to measure atmospheric components of several Jupiter-sized exoplanets, the so-called "hot Jupiters," and now the Neptune-sized GJ 436b. This research was performed before Spitzer ran out of its liquid coolant in May 2009, officially beginning its "warm" mission.

JPL manages the Spitzer Space Telescope mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. Science operations are conducted at the Spitzer Science Center at Caltech. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.